I haven’t always had an interest in computers and technologies. Growing up, that was always more of my brother’s passion— I was more of a legal or political mind. As I mentioned in my About, my interest in computers didn’t start until I was in high school, but it would still take some time before I got really into them. That shift started from (of course) YouTube.

It was some time after finishing college and learning more about effective note-taking that I would get suggested a particular channel: Luke Smith. His videos still hold up incredibly well and offer great insight into both Linux and more minimalist ideology; however, not long after I was daily driving Linux, tweaking my system and everything, he abruptly stopped posting videos. For over two years, his channel sat silent until, out of the blue, he posted a video— several, actually, and he has continued to post rather frequently. Two of his recent videos touched upon a thought experiment he summarized back in one of his from years prior and prompted this whole response from me. But first, a little foreword:

The metaphysics of Input and Output and the Chinese Room Experiment

Several sectors of the economy, especially in tech itself have continued to reduce their hirings with AI likely being a factor to such: if not as a cause, then likely as an alternative. Because of such, there has been a persistent and growing paranoia concerning the advancements of artificial intelligence towards what some see as inevitable, complete sentience. However, debate over artificial sentience and autonomy has raged on for decades.

Since the advent of systematic, computational instruments that could outpace the calculations of professional computers (back when that was a job title for people), curiosity and concern regarding what computers would inevitably become continued to grow. If these artificial computers were able to outperform normal, human people, how long before computers were able to surpass people in other things? How long before computers were equivalent to people? How long before computers surpassed people?

At which point is there really a difference between man and machine?

The famous theoretician Alan Turing approached this very question with a test: have an interrogator question two participants with one being human; the other, a machine. The interrogator is in a separate room and their objective is to determine which of the two is the machine. If a computer can pass for human in this circumstance (like in an online chat), we should accept that there is an indication of intelligence in the machine.

In 1980, John Searle, a University of California Berkeley philosopher, combated this claim by presenting his own thought experiment in a similar vein of that of Turning’s.

Imagine a native English speaker who knows no Chinese locked in a room full of boxes of Chinese symbols (a data base) together with a book of instructions for manipulating the symbols (the program). Imagine that people outside the room send in other Chinese symbols which, unknown to the person in the room, are questions in Chinese (the input). And imagine that by following the instructions in the program the man in the room is able to pass out Chinese symbols which are correct answers to the questions (the output). The program enables the person in the room to pass the Turing Test for understanding Chinese but he does not understand a word of Chinese.

What Searle argues is that just because an AI chat bot can sound like a person doesn’t mean it understands what it’s saying. A similar way to think about this is with something like dogs. On average, dogs can learn about 89 words, like “sit” or “stay”, but do they understand what those words mean? If a dog is trained to sit on command, they understand that the word is an order (input) and that they should sit when told (output), but they don’t understand what the word itself is.

What AI understands is the syntax of language, just like how Googling a question like “How tall is the Empire State Building”1 before AI could still provide you a series of quality answers. The algorithm Google uses breaks down the query and assigns significance to the words and the succession of those words based on general linguistics.

flowchart TD

subgraph Phase1["phase 1"]

subgraph FileSearch["file-search"]

SF[search-files 'foo']

end

subgraph SemanticSearch["semantic-search"]

SI[search-identifiers 'foo'] --> CL[crossref-lookup] --> CE[crossref-expand]

end

subgraph TextSearch["text-search"]

ST[search-text --re='foo']

end

SF --> CR[compile-results]

CE --> CR

ST --> CR

end

subgraph Phase2["phase 2"]

subgraph Display["display"]

AR[augment-results]

end

end

CR --> AR --> OUT[OUTPUT]

What that search didn’t understand and still doesn’t is the semantics of the query: what does the question mean in and of itself?

What’s the Beef with Smith?

I would highly suggest watching the below videos in sequence so you properly understand both the above thought experiment and Luke Smith’s arguments to the fullest. By no means would I want to misrepresent what he says.

Consciousness, Computers, and the Chinese Room

Computation isn’t Consciousness: The Chinese Room Experiment

Consciousness Is Not Material

I began this whole thing with a breakdown of the Chinese Room Experiment to express that Luke and I are on the same page concerning the intent of Searle. Where we differ is exactly how Searle and Daniel Dennett, another American philosopher and cognitive scientist, do: what is consciousness? Luke seems to infer from Searle’s example that consciousness must be non-physical— that it originates from something beyond brain matter or computation. I just can’t help but disagree with this claim.

My argument doesn’t focus on the overview of the mind-body debate, necessarily. I believe the body (and by extension the physical world) has complete influence upon the mind. Luke does concede that there is some facet of mutual linkage between the two: the mind motions the body while physical receptors of the body process things like pain which influence the mind. Instead, what I want to focus on and where I think Smith might be a little misguided is how he attributes semantics to consciousness itself.

What do I mean here? Luke attests that by extrapolating upon this thought experiment, consciousness, in this case that fundamental understanding of what’s being communicated, goes beyond our idea of general computation and is an almost superficial thing. The reason I can’t accept this claim though, at least at face value, is because he just doesn’t explain how one arrives at that autonomy.

Let’s look back at the dog example I mentioned earlier. While a dog may not fundamentally understand the words being communicated, dogs do carry a degree of bodily autonomy: if they’re hungry or they want to play, they attempt to communicate that. It then falls upon us to attempt to process that message and respond adequately. In both of these cases, the subjects are essentially just speaking Chinese to each other; however, they both carry an underlying intention or objective behind relaying/interpreting the information.

In truth, this is how communication operates in general.

When two agents attempt to communicate with one another, there is necessarily a lapse in information as its impossible to completely transmit a message without sacrificing aspects of detail. If we were to look at something like the Switch below, how much would you be able to communicate about the image? While you may describe the color, the shape, or the lighting, there’s some information that cannot be relayed2.

This obfuscation caused by such limits shouldn’t just be applied to speech. Whenever you’re feeling hungry, your stomach transmits signals to your brain that are then interpreted. What exactly does the stomach communicate though? Does the stomach communicate anything at all or is it just our brain that processes that the body needs food? What are the semantics?

We don’t know. Hell, it’s likely our body doesn’t know either. What it does know is that sending certain signals triggers certain responses.

Where I think Luke and Searle might slip— I haven’t read Searle’s work in depth yet so I won’t know for absolute until I do— is to just think that this thought experiment inclusively portrays the cognitive process of consciousness. Responding to input with a determined output is only one aspect of the model that is human consciousness. While the Chinese Room thought experiment is a powerful critique of naive computationalism, it does not affirm dualism or prove consciousness is immaterial. It merely illustrates that syntax alone is not sufficient for semantics.

What we imagine as consciousness, an autonomous entity piloting through life, is so much more than that. Consciousness emerges from a complex web of physiological encoding and decoding. The reason we feel as though we have intention behind our actions and words that we say is because we can’t know exactly what our bodies want; the illusion of consciousness is our brain cognitively filling in for the information lost in the transmission from whatever organ or receptor we have to our heads.

There is absolutely a difference between human sentience and that of AI, without question. We do have an aspect of consciousness that can’t (or at least hasn’t been) replicated through 1s and 0s because we don’t have a complete model of the nearly infinite variables that influence our cognition. But to say that this alone indicates some sort of proof towards that of mind over the body appears fallacious. Even if the Chinese Room fails to show understanding, that doesn’t imply that understanding must come from non-physical sources. It might just mean our model of cognition is incomplete.

I still don’t want anyone to think I’m putting any discredit towards either of them. Searle’s argument is still at the pinnacle of AI and computational theory and Luke Smith is absolutely a great voice on a myriad of topics. I just don’t think the conclusion that Luke arrives at is a concise enough explanation of how the mind and body function. That’s not even mentioning further anomalies like that of the splitting the two hemispheres of the brain.

The Chinese Room shows that syntax alone isn’t sufficient for understanding—but that doesn’t prove consciousness is non-physical. Rather than pointing to dualism, it highlights the complexity of how biological systems process meaning. Our sense of agency may emerge not from a separate mind, but from how the brain interprets incomplete signals from the body. While I respect Searle’s framing and Smith’s take, I see this thought experiment as a call to deepen our physical models of cognition—not discard them.

-

The Empire State Building stands at a height of 1,250 feet (381 meters) to its roof and 1,454 feet (443 meters) including its antenna in case you were curious. ↩︎

-

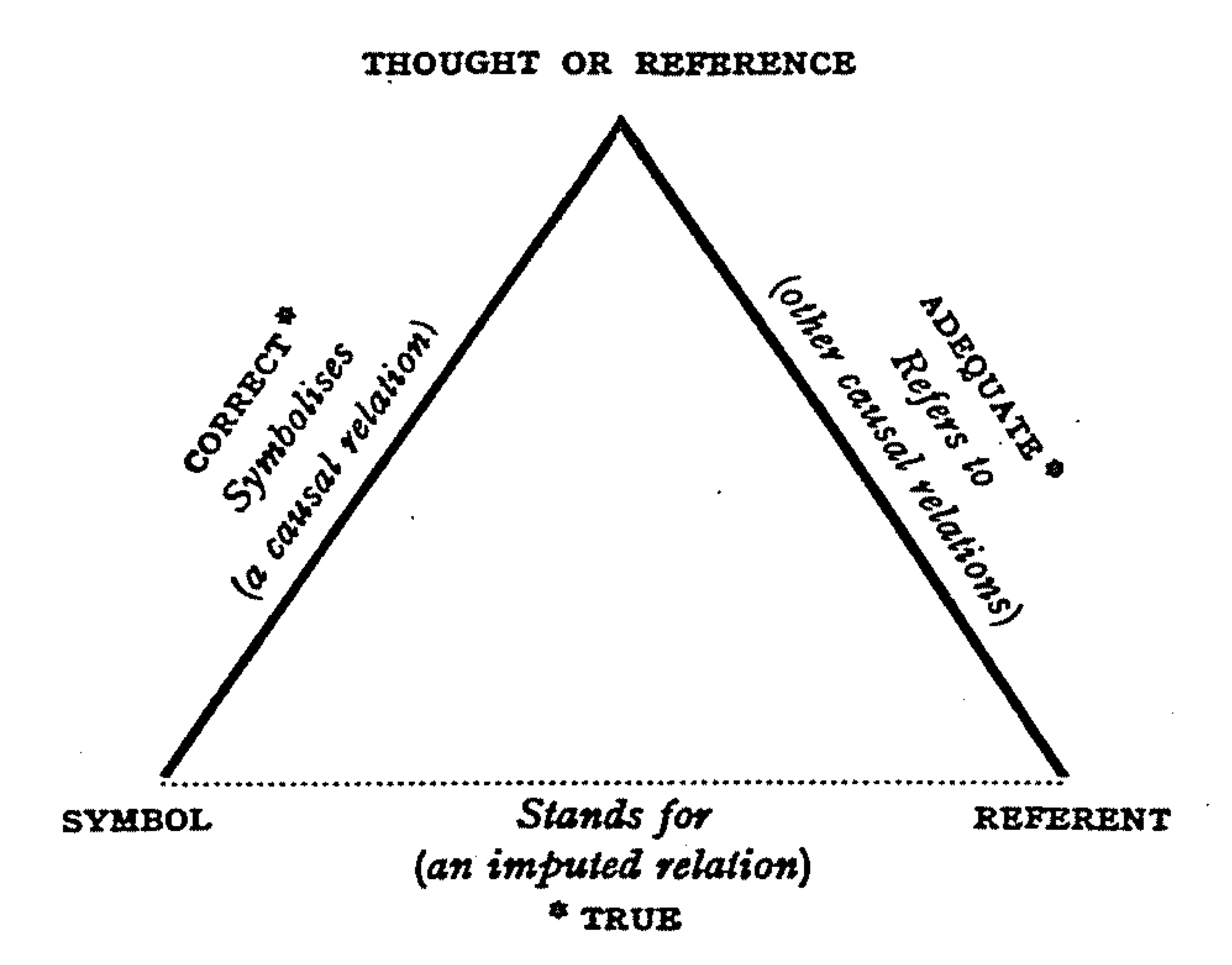

This idea is communicated well through the Triangle of Reference from C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards’ The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism. The triangle illustrates how it’s impossible to accurately describe something (in this case, a symbol) without sacrificing aspects of what you are observing.

↩︎

↩︎